Forgetting to Remember – Lessons from a Vaccine Lost

“It's really easy to forget what it means to live through an outbreak, an epidemic, to face a public health crisis. But when you allow that neglect to pull back on the very control measures that are enabling that success, you're going to see a resurgence, you're going to see that threat come back."

- Dr. Caitlin Rivers

“In a lot of ways, I think part of what we’re seeing is that the loud voices of a few are really drowning out the voices of many who either are not saying anything or are not as loud as all the other noise we’re hearing out there.”

- Maiken Scott

Ever since militaries have existed, some of the most formidable foes were not the opposing forces, but the infectious diseases that swept through camps and troops. The environment that soldiers live in creates the perfect opportunity for pathogens to thrive — close quarters, large numbers, and interactions with people from wide geographic regions.

Adenovirus outbreaks are an example. Before a vaccine, adenovirus infections regularly sickened substantial numbers of troops, resulting in disrupted basic training regimens as well as hospitalizations and deaths of individual recruits. Once a vaccine was available, infection rates plummeted. For 25 years adenovirus infections were no longer a primary concern — but then the vaccine went away, and adenovirus infections reemerged. Forgetting to Remember — Lessons from a Vaccine Lost tells this story.

Watch the film to see what happened and consider the lessons that can be applied to infectious disease outbreaks in communities throughout the U.S.

Identifying a New Foe

Adenoviruses were identified in the early 1950s by two groups working independently. Wallace Rowe, Robert Huebner and their colleagues at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) isolated the virus from adenoid tissues, which led to the family name, Adenoviridae.

Separately, Maurice Hilleman and Jacqueline Werner, researching influenza infections at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, also found the virus in samples they were testing for influenza. Adenovirus is a double-stranded DNA virus that is shaped like an icosahedral with 20 triangles and 12 spikes. These viruses can infect mammals and birds. More than 100 different adenoviruses have been identified; about half of those can infect people. Dr. Hilleman and his team determined that types 4 and 7 most often caused severe outbreaks in people. Outbreaks are most common in places where people gather in close proximity for long periods of time, like military barracks and daycare centers. Young children are among the most susceptible.

Adenovirus infections often occur without symptoms. However, if symptoms are present, they relate to the location of the infection. For example, infections can occur in the upper respiratory tract, causing sore throat, swollen glands and fever, and the eyes, causing pink eye. In some cases, infections can occur in the gastrointestinal tract, causing diarrhea, nausea or vomiting.

Developing a Weapon Against It

With additional knowledge about the virus, attention turned to prevention. The first adenovirus vaccine candidate, made by Dr. Hilleman’s lab at Walter Reed, was grown in monkey kidney cells and administered as a shot. Several inactivated adenovirus vaccines were tested in the late 1950s and early 1960s; however, the inactivated vaccines suffered from variable effectiveness across lots. In 1963, the viruses used for these vaccines were found to be contaminated with a virus, called simian virus 40 (SV40), so use of these vaccines was stopped. Later studies determined that despite concerns about SV40 causing cancer, recruits who received these vaccines, as well as individuals who received other vaccines contaminated with SV40, did not suffer untoward health effects.

Despite this setback, work on adenovirus vaccine development continued because as is often the case, other scientists were working on a different approach. Drs. Couch and Chanock and their colleagues at the National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) had been studying a live adenovirus vaccine that could be given orally. Their approach leveraged an understanding that some adenoviruses infected the gastrointestinal tract without causing illness, so this team coated live adenovirus to protect it from stomach acids. Once in the intestine, the virus would replicate and cause the development of immunity, including following respiratory exposures to the virus. This approach also ran into unanticipated issues in that studies demonstrated that if recruits were only given type 4 adenovirus, the protection was short-lived (about 6-9 weeks) before type 7 started causing illness in vaccine recipients. Ultimately, the scientists were able to resolve this issue by vaccinating against both types 4 and 7, and by 1971 the adenovirus vaccine was being used routinely to prevent outbreaks of adenovirus among recruits.

Notably, even in the 1960s when vaccines weren’t consistently effective across lots, the decreases in hospitalizations and suffering were important. As such, it was cost effective for the military to pursue adenovirus vaccination. By one estimate, the adenovirus vaccine saved the Army about $5 million in 1965.

Routine adenovirus vaccination among military recruits lasted until 1996. As told in Forgetting to Remember – Lessons from a Vaccine Lost, requests for funding to repair manufacturing facilities and remain in compliance with the FDA, went unheeded by the military. As such, the single manufacturer stopped production of the vaccine. The military tried to stretch their remaining supply, but by 1999, the vaccine was gone. Adenovirus rates quickly increased. In 2000, two recruits died, and the military reevaluated the need for adenovirus vaccine. Unfortunately, because it is easier to lose a vaccine than to replace one, it took until 2011 for routine adenovirus vaccination to resume among military recruits. During this interval, a new manufacturer had to be identified and clinical trials conducted before a vaccine could be licensed.

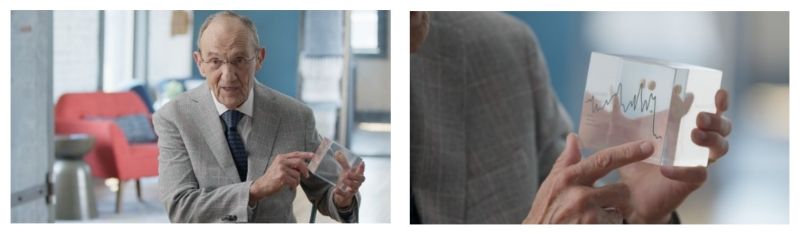

Dr. Joel Gaydos holding adenovirus vaccine tablets in Lucite casing etched with a graph depicting the sharp decline in cases of adenovirus among military recruits after the vaccine was reintroduced.

Turning the Foe into an Ally

Over time, scientists explored the use of adenoviruses as viral vectors. Adenoviruses used as vectors have been modified, so they cannot cause disease, but they can deliver genetic material into cells, such as with gene therapy or a vaccine. One example of the use of this approach was the J&J/Janssen COVID-19 vaccine (no longer available in the U.S.). Watch this animation to see how this, and other viral vector, vaccines work.

Adenoviruses are ideal vectors for a few reasons. First, there is a great deal of scientific knowledge about adenovirus structure and function. Second, adenoviruses are easy to work with in the laboratory. Third, they are effective as viral vectors because they typically result in a strong immune response. Fourth, the technology can be adapted for different uses, such as vaccines (e.g., COVID-19 and Ebola vaccines) or treatments (e.g., Oncorine, which has been licensed to treat nasopharyngeal cancer in China).

Related Resources

- “A Closer Look: The Military and Vaccines – A Shot in the Army” – The Hilleman Chronicle article

- "On Target!" - New York Herald Tribune Cartoon Regarding Dr. Maurice Hilleman's Adenovirus Vaccine – Collection object from the American History Museum

- “Adenoviruses” – Book chapter from Medical Microbiology, National Library of Medicine